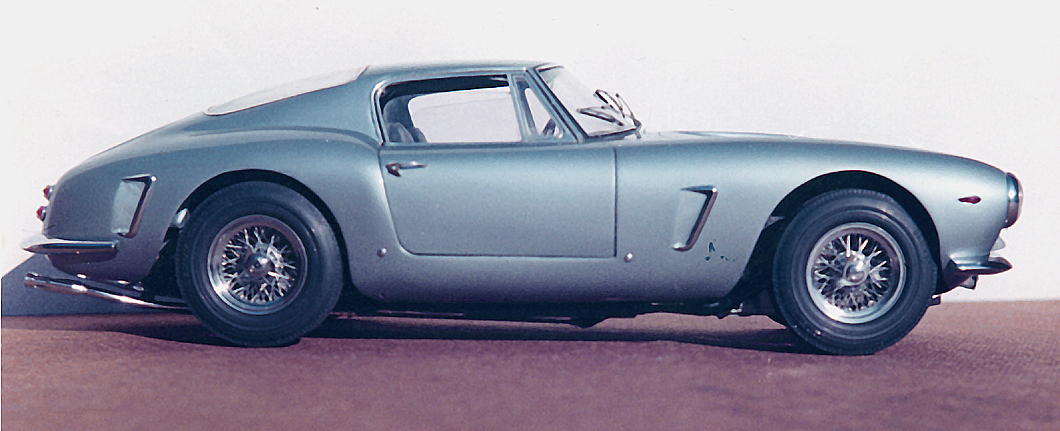

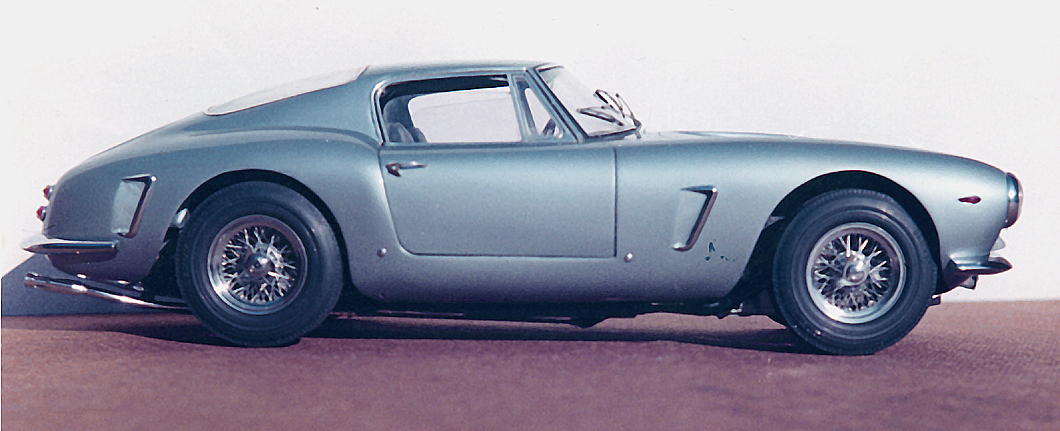

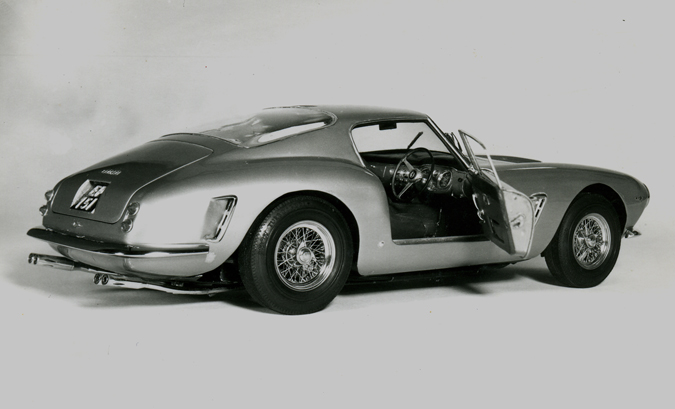

The magnificent model of the 1962 Ferrari Scagliatti 250 GT Berlinetta SWB.

This model was ordered by Lord Edward Portman who had the full-sized car made to his own specification by Ferrari.

above, the steel body-shell nearly complete and a detail of the off-side front wing

The model in the first clear case with switches to control functions, even the wheels rotated.

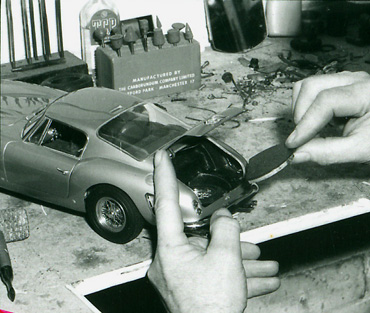

Henri working on the Ferrari when nearly finished, note the spare wheel in the open boot

to see more detail, click on any picture for 2x enlargements

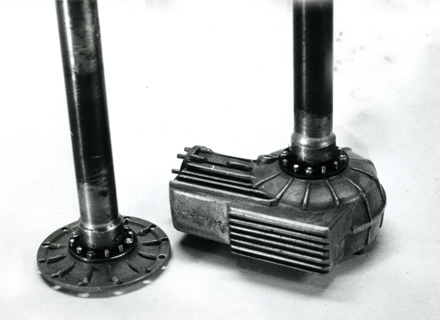

Full-size or not? Chassis before body-shell fitting

The interior was correct in every tiny detail, even the speedometer worked.

suspension and under-chassis details, note the anti-roll bar

Chassis near completion

Details of the fully-working front suspension layout.

gears and internals of working gearbox including synchromesh

the differential assembly, click images for enlargements.

The following article was published in The Playboy Magazine for December 1965 and again in The Best of Playboy No. 5, during 1971.

I have repeatedly asked for copyright permission to include parts of it on this web-site. Making it clear that any proceeds from its publication will be go to the Oxford Transplant Fund which is a registered charity. My first request by letter was on 9th March 2007, and I followed this with others. Eventually, I sent an email to copyright@playboy.com. I received a reply email from them on 28th January 2008 saying that a full answer to me should be available by early the following week. I have heard nothing since. I emailed the person again on 16th September. No answer! So I suppose the lady involved has moved on. I am hoping that they will not force me to withdraw it from such a worthy cause.

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING FERRARI

Article By Stirling Moss

Britain’s motor-racing great describes in loving detail the most unusual automobile he’s ever seen

THERE'S THIS FERRARI 250 GT—beautiful job, finished in metallic blue-gray with blue leather upholstery, V-12 engine with three twin-choke Webers, twin distributors and fuel pumps and ignition systems, four-speed all-synchro gearbox, Borrani wheels with four new Avon Turbo-speed tires, heater, power brakes, one careful owner from new, an absolute steal at $12,600—and it’s just over a foot long. That comes out to about a thousand dollars an inch!

This particular Ferrari wasn’t made by the Commendatore’s men at Modena, but by Mr. Henri Baigent in Bournemouth, England. That doesn’t make it any less exotic, however. In fact, it’s the most incredible Ferrari I’ve ever seen anywhere, and I’ve seen a few in my time.

The story really began for me when I met Baigent during the days when I was driving Grand Prix cars for Rob Walker. After experience in aircraft engineering and later in instrument making, Baigent had turned to model-making—as an art and as a means of earning a living. One of the first models he made used a three-cylinder in-line working engine that he later put in a model Aston he built for Walker. At the time I met Baigent, he was busy making a model of the Cooper I drove for Rob; it was later given to me, and now resides next to my desk, a snug glass Case protecting its delicate works from prying hands.

Some years ago, I heard that Baigent was engaged in making a model Ferrari for British sportsman Eddie Portman; it was to be a replica of Portman’s own car, and nothing was to be spared in making the model as accurate and detailed as possible. I’d seen Baigent’s work at firsthand, so I had some idea of the standard of workmanship to expect, but I didn’t have a chance to see the car until it was returned to Baigent a month or so ago for some minor repairs and he offered to show it to me. Well, I finally clapped eyes on it the other day and I was absolutely flabbergasted. I had never in my life seen anything so perfect—it was as if every part of the real thing had been scaled down by some scientific process, perfectly and without distortion. Photographs alone can’t do the model justice, so I’ll try to describe the car in detail, so I'll let you judge for yourself whether it’s worth the price.

Normally, Baigent likes to have a good look at the car he’s going to copy, even if he later has to work from drawings or photos; he says it’s the only way to make sure that he can properly capture the essential character of the car. In this case, he was lucky in that he was able to work from the actual car from start to finish, but even this created difficulties of its own. The chassis, for instance—have you ever tried to find the chassis of a Ferrari? The only solution was to crawl under and over the car, painstakingly measuring everywhere to establish the precise shape of the chassis. This was reproduced exactly with welded metal tubing, to form a basis for the rest of the model. Next came the suspension, with all parts made to scale and, more important, working properly, too. Not only were the coil springs the right size and shape. but they deformed by the right amount when they were loaded. Steering gear, too, worked the same way it did on the original, with proper geometry and gearing ratios. The wheels carry correct brake disks with working callipers made to be powered by compressed air; the knock-off wire wheels really do knock on and off; they have proper splined hubs and their spokes are properly graduated, being thicker at the hub than at the wheel rim. And naturally, the spare wheel is interchangeable with the others. The tires were made by Baigent in moulds he himself constructed, using a mixture of high-cling rubber, supplied by Avon itself, that was identical with that used in the original tires.

The engine is extraordinary; and not only is its exterior perfect, with all the components and auxiliaries exactly reproduced (including the alloy carburetors with polished air intakes and the crackle-finished cam covers with raised fins and the name Ferrari embossed on each of them), but all the moving parts inside work as well. The radiator in front of the engine is made up of 160 separate leaves and contains 48 tubes, all so carefully made that the whole system will hold water under pressure.

The clutch works, too, and the gearbox is enough to make you disbelieve your own eyes. Not only are all the wheels made to scale from the actual box, with working synchromesh on all forward speeds, but the selector mechanism is there, too, so that you can change gear by using the immaculate model gearshift. All the nuts and bolts on the box itself and on the inspection plates are to scale and workable—and the gear teeth are surface-hardened to minimize wear, just as they are on the real thing.

The differential end of the transmission setup has been handled with similar care. At one stage, Baigent thought of having the crown wheel specially made, and asked for a cost estimate from a famous precision engineering firm. They quoted a price of $420 for the wheel, including $140 in drafting charges alone, and said the job would take months. So Baigent, doing all the cutting and hardening, made it himself—in two days.

The body is hand-beaten in thin metal, though Baigent admits that the metal is thicker than scale. To be accurate in this respect would have meant a very fragile body, and the effect of clumsy hands picking up the model would have been equivalent to a nasty shunt in the real thing. Also, very thin metal wouldn’t have taken the exact shape so well. But most people couldn’t tell the difference without a micrometer; I know I couldn’t. All the doors and the trunk lid have scale-model working catches, the doors having a second catch to stop their flying open at speed. Door checks prevent them from slamming shut once they’re opened, and the trunk lid stays up of its own accord, giving access to the carpeted trunk and to the spare-wheel locker. The bumpers, air intake and head-lamp rims and door handles are all made from chromium plate, but chrome plating proved too brittle for the windscreen and window frames, so these were hand-beaten from solid silver. The windows were moulded by Baigent, as were the head-lamp lenses, which have the correct relief patterning on their front.

The carpeting and headlining inside the car are original-perfect. The seats were made from the remaining pieces of the leather used in the real Ferrari and, besides being impeccably shaped, they’re correctly sprung. The crackle-finished dashboard contains a full set of instruments with authentic-looking glass dials, and a full set of switches, too. The three-layered steering wheel has alloy spokes, the proper Nardi insert (this was a long time in the making, as the wooden rim sections had to be turned by hand and kept breaking before they could be fitted onto the metal insert) and the famed Ferrari prancing horse on the horn button. The doors have working handles on the inside and the windows wind up and down, while the leather pockets in the bottom of each door, made from the same skins as the seats, are authentically elasticized.

The immaculate exterior paint work has been sprayed on, with the paint— supplied by Ferrari—used on the original car. The Ferrari badge on the front of the hood is a perfect replica, even when seen through a magnifying glass.

But I’ve saved the best for the last. The model is designed to be displayed on a special rotating stand. The wheels are mounted on rollers, and the stand rotates slowly to give an all-round view of the model. An electric motor on the stand drives the model’s engine through a universally jointed drive shaft; there is a cable that carries power to a two-volt transformer, which in turn powers all the model’s electrical equipment. This means that when the power is on, you can drive the engine of the car, working the clutch, gearbox and final drive in the proper manner. You can brake, and you can steer the car with the steering wheel. Not only that, but you can switch on any of 30 lights in the car, from the special three-volt head-lamp bulbs to courtesy lights and lights in the instrument dials. The directional signals work from switches on the dashboard and the head-lamp flasher is operated from the steering-column control; the twin horns work, too. Brake lights function when the brakes are used, and the windscreen wipers are driven by their own tiny motor, hand-wound by Baigent and fitted carefully under the hood. And, most fantastic of all, the speedometer and tachometer actually work, with the former showing the speed at which the rear wheels are turning on the rollers and the latter indicating the engine revolutions—these on dials about as big as the head of a pushpin (the tachometer has to contain a solenoid and three bulbs in that space). There’s also an electric heating element, fan and thermostat that keep the inside of the model at a steady 75 degrees for the comfort of driver and passenger.

And before you say that $12,600 is a lot of money to pay for any model, even one as incredible as this, let me point out something. Even though you could buy a pretty good used Ferrari for that much money. just bear in mind that the model took 11,000 hours to build—over three and a half years of hard, highly skilled effort to produce a creation of real beauty. Ferrari himself doesn’t make them that carefully.

Mind you, this model is something out of the ordinary even for Baigent; normally, he doesn’t spend that much time on a model, but he was anxious to make this one unique. He usually doesn’t make more than one model of a particular car, though he has made other Ferraris, such as the beautiful model of driver Innes Ireland’s GTO he did for the Rosebud racing people. But he won’t make another Ferrari to the 250 GT standard, although he might produce a similar model of another make if someone asks him to. His next model will be a replica of Tommy Rose’s vintage Le Mans Bentley. and I, for one, can’t wait to see it. I think Baigent prefers to make models of the older cars, since you can see the workmanship that goes into them more easily. Most of the fantastic work that’s gone into the Ferrari, for instance, is hidden by the beautiful bodywork, and you don’t realize what’s there until it’s all explained to you. In that respect, Baigent told me that a Rolls-Royce Ghost is the one he really wants to duplicate. I only wish I could afford to commission it—the result would certainly be worth seeing.

above, article from Autocar 27th May 1966, click to read

above, article from Model Cars Nov 1965, click to read

cuttings of an article from a German newspaper, click images to read

Approximate translation into English.

"The dearest car according to size is not a Cadillac or Rolls Royce or the

great Mercedes, but a Baigent.

You have never heard the name? No wonder, Baigent’s model cars are costly rarities.

The English builder of model cars recently outdid himself with a Ferrari 250

GT of one-twelfth scale which is almost as dear as the full-size Italian car.

Baigent’s true-to-life reproductions cost more than 50,000 marks per centimetre of model car which is 36 centimetres long, that is 1,400 marks.

Henri Baigent, the builder of the most expensive car lives in the English

resort of Bournemouth.

His factory is an old shed. Earlier in life Baigent worked as a fireplace builder.

In the war he made precision instruments for military aircraft. This work on

instruments was the basis for the car reproduction of today.

What makes Baigent’s car so expensive?, all materials are as in the full-sized car, whether it is in the wheel construction or the casting of the engine block.

And who buys such a Super-Toy? The Ferrari was made for the British racing-motorist Edward Portman (33) who is a multi-millionaire.

‘I love cars and I have owned many but to me the Ferrari was the best. So I had the idea of having a model made of it, one as exact as possible, and for this there is only one man.’ Portman lovingly strokes the car. It stands on the mantelpiece of his country house in a valley of the English county of Herefordshire. The insurance alone for the mantelpiece racer amounts to 1,500 marks per year, not too much when you think that there was three and a half years work in the Ferrari reproduction."

.. and some other national press cuttings

article from the French magazine Modelisme Dec 67-Jan 68 No. 56

click on images to read in French

Approximate translation into English (to be added when time permits):